Teagasc Crop Report

Tillage Grass Weeds

Tillage Grass Weeds

To view the full report you must have an existing account with Teagasc ConnectEd.

Farmers sign in hereAlready have a ConnectEd account? Connected Client or Teagasc staff log in here

Grass weed identification

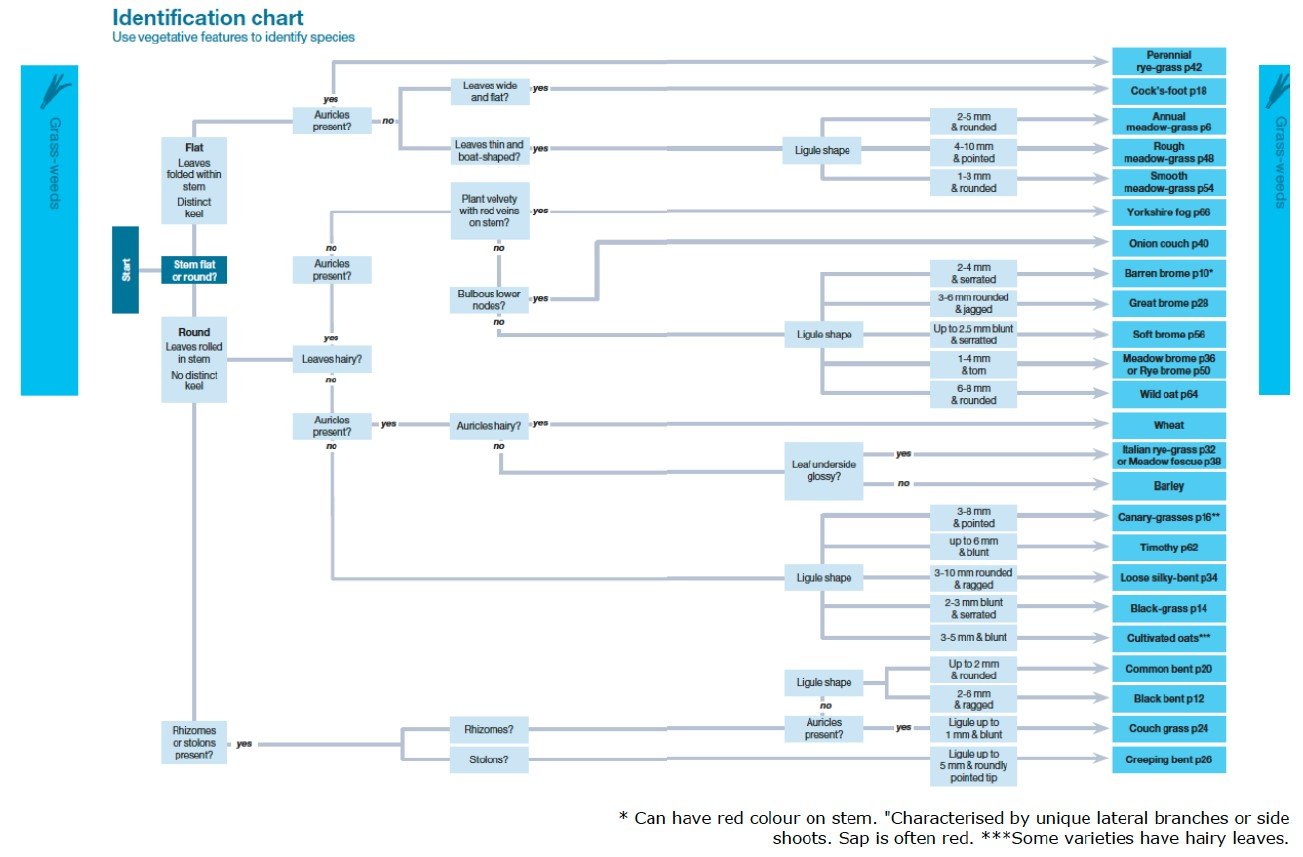

Before deciding on how to control a weed, first it must be accurately identified and its growth pattern and biology understood, this will enable you to develop the right strategy that will give you sustainable and cost effective control.

Identification

Grasses have many common characteristics that can be used to make an accurate identification. When identifying grass weeds look out for these main characteristics:

- the presence of rhizomes and stolon’s

- whether the leaves are rolled or folded within the stem

- the presence and appearance of the auricles

- the presence of hairs on the leaves and leaf sheaths the shape of the ligule

- the structure and appearance of the seed head

Using a guide such as the BAYER weed guide is a useful tool to help identify many of these weeds as it provides a structure to the identification process. See the picture below which uses plant features to identify the species.

Source: BAYER Weed Guide

There are many other characteristics which are less common and maybe more distinct to individual species such as a reddish/purple colour at the base of the stem or on the leaf sheath, characteristics of the leaves, such as colour and twists in the leaves. These are very useful to know but as there are many it is maybe not practical to be familiar with them all.

See here for more information

Wild oats

There are two types of wild oats. Avena fatua (Spring wild oat) and Avena sterilis (Winter wild oat). Fields generally have spring wild oats but occasionally fields can have a mix of spring and winter wild oats.

Identifying both species (See pictures here)

Avena fatua (Spring wild oat)

- Awns present on third seed within spikelet

- Seeds separate when mature and shed singly

Avena sterilis (Winter wild oat)

- Awn absent on third seed in spikelet

- Seeds remain attached when mature and shed as a unit

Spring wild oats

This is the most common type of wild oat in Ireland.

- Predominately spring germinating, but odd seedling germinate from September to May.

- Have the ability to survive in soil for several years and thus unaffected by seed burial depth.

- Plants set seeds from Jun to Oct and light promotes germination.

- Most seeds emerge from the top 10 cm soil, but some emerge from greater depths, up to 15 to 25 cm.

- A single well-tillered plant has the ability to produce up to 2,000 seeds.

- A population of 1 plant per m2 has the potential to cause a yield loss of 1%

There is now confirmed Herbicide Resistance to most of the major herbicide types

Brome

Sterile brome is the most common grass weed of the brome family. However Soft, Great , Meadow and Rye brome are present in many Irish fields also.

Correct identification of these bromes is critical to achieving good control. Each brome has specific identifying characteristics with identification becoming easier when the plant is headed with mature seeds.

Sterile Brome

Sterile brome is the most widespread weed, found with a range of fertile soils throughout Ireland.

Sterile brome is native and widespread in Ireland. It’s not hard to recognise as its familiar purple, drooping heads are seen towering above cereal crops and around hedges each June and July. It’s an annual grass weed which means a plant must germinate from a seed every year. Its natural habitat includes verges, field headlands and waste ground. It grows freely on waste or cultivated land on well-drained soils. It is competitive in winter wheat and winter oilseed Rape. It can cause a yield reduction in wheat of 2.4% with just 3 plants/m2. It is increasing problematic on arable land that is in continuous cereals especially winter barley where herbicides options are minimal. Brome has no auricles.

Scientific classification:

|

Kingdom |

Plantae |

|

Family |

Poaceae |

|

Genus |

Bromus |

|

Species |

B.sterilis |

Key identification features

Sterile brome from a young plant has a hairy stem and leaves, it has a dense covering of hairs on the stem and leaf surface. It is easy to spot in barley crops due to its twisted slender leaf appearance; it is more difficult to distinguish from wheat crops due to the twisted leaf and slender leaf structure of the wheat plant. The key feature to look for is the hairs on the stem and leaf, a magnify glass is sometimes required to see the hairs especially on young plants. It helps to roll the leaf over your finger and hold it up to the light to see the surface of the leaf hairs.

It must be noted that all bromes have hairs so furthermore identification may be required, if possible finding the seed that the plant emerged from can be a good indicator but it is sometimes hard to differentiate between the different bromes.

The ligule is like a barcode for grass weeds, the ligule of each plant differs allowing for accurate identification. To find the ligule of a plant is quite simple, it can be seen at the stem where the leaf has the left the stem.

Key features

- About 90 % of sterile and great brome germinates from Aug to Dec; it flowers from May to Jul and shed seeds from Jul to Aug.

- Other bromes, especially soft (relic of Irish grassland), meadow and rye germinate in the autumn, but also in early spring.

- Sterile and great brome requires vernalisation to produce seeds and these readily germinate in darkness, while soft, meadow and rye brome seeds require a period of post-harvest ripening and light to induce germination.

- Sterile brome

- Can produce and average of over 200 seeds but this can range from 5- 300 seeds per plant.

- Seeds have poor persistent in the soil.

- Seed emergence is reduced with increasing seed burial depth (> 10 cm).

- 5 plants per m2 can cause yield reduction of 5 %.

Seeds statistics;

- Seed longevity >1 -5 years

- Seed decline > 90% per year

- Germination depth > Once the seed is covered up to 5cm deep

- Flowers per plant > 4 - 10

- Seeds per flower > 200

- Seeds per plant > up to 2000

Great Brome

Scientific classification

| Kingdom | Plantae |

|---|---|

| Family | Poaceae |

| Genus | Bromus |

| Species | B.diandrus |

Description

Great brome has been found in some areas of Ireland but is not as dominant as sterile brome. However its often underreported partially due to mistakenly identified as sterile brome in some cases. Similar to sterile, great brome is found in field margins, waste ground and roadsides. It usually prefers a sandy soil and dunes.

Herbicide Resistance

- Herbicide resistance is defined as ‘the evolved ability of a weed population to survive a maximum dose rate of herbicide that was previously known to be lethal’.

- Resistant weed populations may by-pass the herbicide action by two mechanisms: target-site resistance (TSR), where simple mutations prevent the herbicide from binding effectively to its site of action and non-target site resistance (NTSR), where complex multigenic changes, allow the weed to metabolically detoxify or degrade the herbicides to an extent where they are ineffective.

- Resistance is further exacerbated by the lack of alternative herbicide types, forcing growers to repeatedly use the same active ingredients.

- Herbicide resistance is a global problem with 500 unique resistance cases being reported, globally until 2019.

- Herbicide Groups A (ACCase) and B (ALS) pose a very high risk of resistance.

- NTSR has been reported to be the common type of resistance to glyphosate, and also plays a key role in resistance to ACCase and ALS inhibitors. Although, NTSR is slower to develop, NTSR resistant weeds are widespread in major tillage crops. For example, chlorotoluron and pendimethalin actives can affect NTSR to some degree.

- Herbicide resistance can also occur through spread of resistant genes, in contrary to independent-endowing mutations.

- Sensitivity tests are valuable to provide direction to correct management strategies

Wild Oat (Avena fatua) herbicide resistance

Spring wild oat populations were tested for resistance to ACCase inhibitors pinoxaden (DEN or Axial) , propaquizafop (FOP or Falcon) and cycloxydim (DIM or Stratus Ultra) was investigated in populations of six Spring wild oats, Avena fatua collected from cereal-dominated rotations in Ireland.

Glasshouse assays confirmed reduced sensitivity to all three ACCase inhibitors in four of the populations tested. R1 population was cross-resistant to pinoxaden and propaquizafop and R6 was resistant to propaquizafop only.

Dose-response studies confirmed significant differences in resistance levels amongst these populations (P < 29 0.05).

- For pinoxaden, the ED50 or GR50 resistance factor (RF) of population R1, R3 and R5 were between 11.6 and 13.1 times or 25.1 and 30.2 times more resistant, respectively, compared with the susceptible populations.

- For propaquizafop, the ED50 or GR50 RF 32 of populations R1, R2, R3, R5 and R6 were between > 7.8 and > 32 or 16.6 and 59 times more resistance, respectively compared with the susceptible populations.

- For cycloxydim, only population R5 had both the ED50 and GR50 RF exceeding > 43.2 and 98.4 times compared with the susceptible populations.

In population R2, although the ED50 values to both pinoxaden and cycloxydim and additionally, population R3 to cycloxydim, were above recommended field rates, their GR50 values remained below, suggesting a shift towards cross resistance.

While population R4 was the only population, where both ED50 and GR50 for all ACCase inhibitors remained below recommended field rates, but they would not give effective control at these rates, strongly indicating evolving resistance.

This is the first study reporting variable cross-resistance types and levels to ACCase inhibitors in A. fatua from Ireland.

The full results are available here

Please create an account to view hidden content

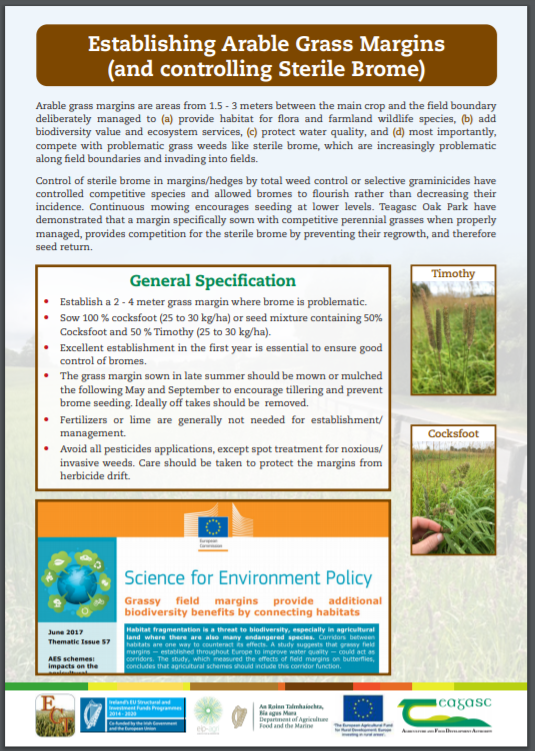

Grass Margins - Arable fields

Arable grass margins are areas from 1.5 - 3 meters between the main crop and the field boundary deliberately managed to (a) provide habitat for flora and farmland wildlife species, (b) add biodiversity value and ecosystem services, (c) protect water quality, and (d) most importantly, compete with problematic grass weeds like sterile brome, which are increasingly problematic along field boundaries and invading into fields. Control of sterile brome in margins/hedges by total weed control or selective graminicides have controlled competitive species and allowed bromes to flourish rather than decreasing their incidence. Continuous mowing encourages seeding at lower levels. Teagasc Oak Park have demonstrated that a margin specifically sown with competitive perennial grasses when properly managed, provides competition for the sterile brome by preventing their regrowth, and therefore seed return. Click on the picture below to read more.

Grass Weed Susceptibility Table - Cereals Pre Emergence

Please create an account to view hidden content

Glyphosate: Avoid the resistance risk

Glyphosate is a non-selective herbicide used to control annual and perennial weeds. Worldwide over 50 species of weeds have had populations with glyphosate resistance. In Europe, glyphosate resistance has typically been selected in permanent perennial crops such as orchards and vineyards.

Glyphosate-resistant ryegrass populations have also been found in cereal crops in Ireland in 2024

Glyphosate-resistant ryegrass populations have also been found in cereal crops in Italy.

Glyphosate, when applied correctly, remains an essential component of integrated weed management (IWM), preventing challenging grass weeds taking over fields. It is particularly relied upon in stale seedbed systems which are essential for any non-inversion tillage system and is good practice in plough-based systems too.

Glyphosate rates and application timings are critical in avoiding resistance build-up.

Please create an account to view hidden content